Faced with the intensification of droughts and the gradual depletion of conventional resources, Morocco has made seawater desalination a key component of its water strategy. Once considered a supplementary solution, desalination is now expected to simultaneously secure agricultural irrigation and drinking water supply in several regions of the Kingdom.

The Moroccan agricultural model, heavily oriented towards exportation and based on high-value-added sectors—such as citrus fruits, berries, and greenhouse vegetables—depends closely on regular access to water. However, reservoirs and aquifers are no longer sufficient to ensure this stability. In this context, the use of desalinated water emerges as a strategic alternative to maintain the competitiveness of the sector while supporting urban expansion.

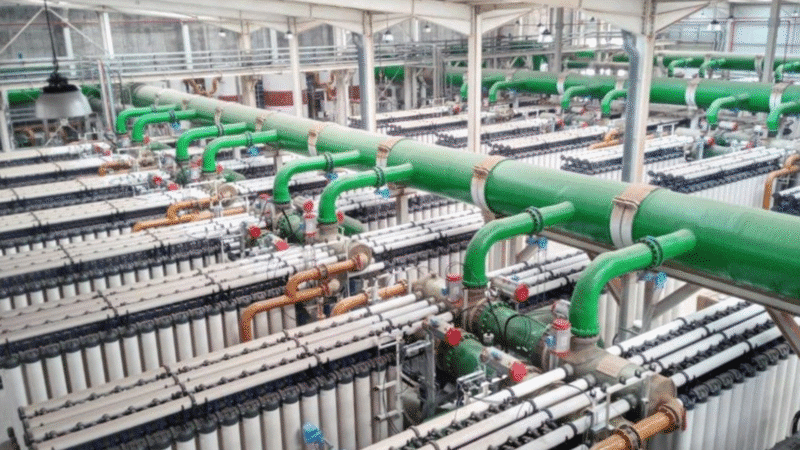

Since 2020, the state has launched a vast investment program under the National Drinking Water Supply and Irrigation Program, mobilizing over 115 billion dirhams by 2027. Several desalination plants have been constructed or are underway to enhance water security for cities like Agadir, Laâyoune, and Casablanca. The Agadir plant, capable of producing 275,000 m³ per day, exemplifies this growth. It supplies both the drinking water network and nearly 15,000 hectares of irrigated crops.

However, this strategic direction comes with a high cost. Building desalination units requires massive investments, often estimated in hundreds of millions of dollars. Additionally, operational costs are heavily dependent on energy. Producing one cubic meter of desalinated water requires between 2.5 and 3 kilowatt-hours of electricity. Despite technological advances in reverse osmosis, production costs remain between 0.40 euros and over one euro per cubic meter, depending on the context.

In Morocco, the gap between the actual production cost and the price charged to consumers creates significant budget pressure. The average cost of producing drinking water far exceeds the tariffs applied to the lower tiers of domestic consumption. This distortion necessitates a public subsidy mechanism to bridge the gap. In Agadir, for example, the state compensates the difference between the purchase price from the private operator and the distribution tariff, resulting in several hundred million dirhams over a few years. In Laâyoune, the difference between the actual cost and the applied tariff also generates a significant deficit.

Beyond financial considerations, the energy issue remains central. The majority of electricity used for desalination still comes from fossil sources. This dependence increases the carbon footprint of the plants and heightens vulnerability to energy price fluctuations. Therefore, the gradual integration of wind and solar energy is essential to ensure the environmental sustainability of the model.

Another challenge is the management of brine, a highly saline waste byproduct from the filtration process. Its discharge into the sea can affect coastal ecosystems if dilution and dispersion conditions are not controlled. The expansion of desalination thus imposes a rigorous environmental framework to mitigate impacts on marine biodiversity.

Desalination has now become a pillar of national water security. It presents a powerful lever to preserve irrigated agriculture and support urban growth. However, its large-scale deployment raises a complex equation, intertwining financial sustainability, energy transition, and protection of natural environments. More than a technical solution, it has become a strategic choice shaping the future of the Kingdom’s water resources.